A flower's fragrance declares to all the world that it is fertile, available, and desirable, its sex organs oozing with nectar. Its smell reminds us in vestigial ways of fertility, vigor, life-force, all the optimism, expectancy, and passionate bloom of youth. We inhale its ardent aroma and, no matter what our ages, we feel young and nubile in a world aflame with desire.- Diane Ackerman, A Natural History of the Senses, 1990, p. 13

Now, after pouring out a few articles on some popular flowers, it may seem like a wee bit late to broach the question: what are flowers and what purpose do they serve? But then information/ knowledge, how-so-ever hind sighted it may appear, is never too late:-)

It is surprising that many a times what experts in a particular field take as a matter of routine or a very basic piece of information, is a source of amazement to others. And flowers, besides evoking joy and wonder by their varied forms and colors, can be a constant source of amazement to people who did not pay attention in their biology classes:-) and even more to those who sat attentively and took notes.

So, what is a flower? It is a plant's tool to make more plants. In most flowers, the bright colors and beautiful forms of the flower that attract us serve that very purpose----attract---although their target is very different. The color and the fragrance in a flower attracts insects, which help in pollination of the flowers leading to fertilization and fruit and seed set. Flowers that solely rely on wind for pollination (anemophilous) are generally not very showy. Whichever be the case, flowers serve as the reception area for head quarters of the seed manufacturing factory.

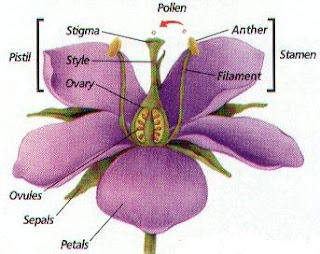

But let me start at the beginning. A typical flower that we might encounter on an ornamental plant, starting at the base, stands on a stalk or a pedicel. There is a whorl of green colored sheath or petal like structures which are called the sepals. Sepals cover and protect the floral structure as the flower develops. A whorl of brightly colored (not necessarily though) petals follow the sepals. Next comes a whorl of stamens standing in attention, that form the male part of the flower. Stamens comprise of long filaments topped by anthers which are generally bi-lobed sac like structures. Inside these anther sacs is the pollen, dreaded by many as the instigator of hay fever. Each anther sac contains millions of pollen grains. If you shake or just pat the inside of a mature flower, you will observe a yellowish powder sticking to your hand. This is the pollen which germinates and carries the sperm cell inside the female part. The central part, like in any good story, is occupied by pistil/carpel or the female flower part. The pistil can be divided into three parts: the uppermost part called the stigma forms the lodging center where the pollen is deposited and sticks; the stigma sits on top of a style, a tubular structure that is traversed by a germinating pollen grain carrying the sperm cell. The style ends in the ovary which carries the ovules. Depending on the flower, there may be single or a number of ovules inside the ovary. The egg cell is present inside the ovule and after the fertilization by the sperm cell (from a germinated pollen grain) takes place, the ovule develops into a seed, ensconcing the embryo for a future plant.

Having served its purpose, the flower folds its office; the petals and sepals wither and fall off and the place is taken by fruit, bearing the seeds. But the flower has numerous stories to tell, many secrets to share and I will dwell on these stories and secrets of the flower.

Unlike animals, plants and therefore flowers are rooted to a place. So they have to make sure that their reproductive paraphernalia is sophisticated and at the same time simple enough to achieve the end result. A large proportion of the flowering plants (about 70%) are bisexual, meaning that both the male and female parts are present in the same flower. What could be more convenient? You have the anthers churning out the pollen, you have the prim pistil taking the center stage and Viola!!! the plant is ready to produce seeds in huge numbers. These flowers, in botanical world, are the monoclinous or perfect flowers and what better to exemplify this class than the rose. Lilies and viburnums are also perfect flowers.

If there are perfect flowers, there have to be imperfect flowers. These are the unisexual flowers that have either the male or female organs. The botanists choose to call these flowers as imperfect or incomplete. Unisexual, imperfect and incomplete-how well this descriptions fits most of us! Many a non-botanists have planted the seeds for papaya and waited endlessly for it to fruit without realizing that the plant is producing only male flower and will never bear fruit. What is more damning for survival as a species than to be rooted to one place and have no female company! But nature is wily and the process of evolution very, very adamant. So there are plants that may bear unisexual flowers......but then they bear both sexes on different branches. Such plants are called monoecious. Better to have some company than none!! Corn, birches, pines are examples of monoecious plants. The pollination amongst these flowers is aided by insects and wind.

One would imagine that the species in which the unisexual flowers occur on different plants altogether would be the most confounded. These plants are called dioecious and include such plants as hollies and papayas. With cultivated/ornamental dioecious plants, one has to make sure that the male and female flower bearing plants are in close vicinity to allow wind/insect pollination in order to set the fruit and seed.

So, there are perfect and imperfect flowers and amongst imperfect there are monoecious and dioecious flowers. It seems that there is a high chance of inbreeding in the perfect flowers , what with the reproductive organs lying in close proximity. Inbreeding, as we all know, is bad news as it limits the variability in the genepool and weakens the chances of survival for a species. Since the time ofDarwin

The unisexual flowers, of course, allow the mix and match of the pollen and stigmas to enhance the variability in the gene pool. This method poses some constraints like the necessity of closer proximity but is by and large an effective solution. An easier way to ensure cross fertilization is found in plants in which the male and female parts mature at different times. In protandrous flowers, the male organs mature first and shed the pollen before the pistils mature; example Alstroemeria aurea. On the other hand, there are protogynous flowers in which the female organs mature first and they have to be cross fertilized. e. g. Magnolia.

Structural modifications that limit the access of pollens to the stigma of the same flower are also effective in curbing self fertilization. Two lipped tubular flowers from families such as Bignoniaceae and Orchidaceae show bilateral symmetry in which the stigma is positioned right at the entry of the flower causing nectar seeking insects carrying pollen from other flower to affect cross-pollination.

The most sophisticated systems for cross pollination, though, involves a biochemical reaction wherein a chain of reactions ensues after the pollen from the same flower lands on the stigma. The reactions not only recognize that the pollen is from the same flower, but also prevent its further development. Its almost like fingerprinting and arresting the terrorist right at the airport but much more efficient!!

So, the flowers at one level or the other, truly are the charmers that they set out to be. Not all of them are as flamboyant as some of the orchids or as appeasing as the lilies, but they do achieve the end-goal, the purpose for which they are set-forth, i.e. to make more like their own! But all coins have two sides; the beautiful flowers, too, have their counterparts that are neither beautiful nor fragrant. I shall tell their stories next time.

Now, after pouring out a few articles on some popular flowers, it may seem like a wee bit late to broach the question: what are flowers and what purpose do they serve? But then information/ knowledge, how-so-ever hind sighted it may appear, is never too late:-)

It is surprising that many a times what experts in a particular field take as a matter of routine or a very basic piece of information, is a source of amazement to others. And flowers, besides evoking joy and wonder by their varied forms and colors, can be a constant source of amazement to people who did not pay attention in their biology classes:-) and even more to those who sat attentively and took notes.

So, what is a flower? It is a plant's tool to make more plants. In most flowers, the bright colors and beautiful forms of the flower that attract us serve that very purpose----attract---although their target is very different. The color and the fragrance in a flower attracts insects, which help in pollination of the flowers leading to fertilization and fruit and seed set. Flowers that solely rely on wind for pollination (anemophilous) are generally not very showy. Whichever be the case, flowers serve as the reception area for head quarters of the seed manufacturing factory.

But let me start at the beginning. A typical flower that we might encounter on an ornamental plant, starting at the base, stands on a stalk or a pedicel. There is a whorl of green colored sheath or petal like structures which are called the sepals. Sepals cover and protect the floral structure as the flower develops. A whorl of brightly colored (not necessarily though) petals follow the sepals. Next comes a whorl of stamens standing in attention, that form the male part of the flower. Stamens comprise of long filaments topped by anthers which are generally bi-lobed sac like structures. Inside these anther sacs is the pollen, dreaded by many as the instigator of hay fever. Each anther sac contains millions of pollen grains. If you shake or just pat the inside of a mature flower, you will observe a yellowish powder sticking to your hand. This is the pollen which germinates and carries the sperm cell inside the female part. The central part, like in any good story, is occupied by pistil/carpel or the female flower part. The pistil can be divided into three parts: the uppermost part called the stigma forms the lodging center where the pollen is deposited and sticks; the stigma sits on top of a style, a tubular structure that is traversed by a germinating pollen grain carrying the sperm cell. The style ends in the ovary which carries the ovules. Depending on the flower, there may be single or a number of ovules inside the ovary. The egg cell is present inside the ovule and after the fertilization by the sperm cell (from a germinated pollen grain) takes place, the ovule develops into a seed, ensconcing the embryo for a future plant.

Having served its purpose, the flower folds its office; the petals and sepals wither and fall off and the place is taken by fruit, bearing the seeds. But the flower has numerous stories to tell, many secrets to share and I will dwell on these stories and secrets of the flower.

Unlike animals, plants and therefore flowers are rooted to a place. So they have to make sure that their reproductive paraphernalia is sophisticated and at the same time simple enough to achieve the end result. A large proportion of the flowering plants (about 70%) are bisexual, meaning that both the male and female parts are present in the same flower. What could be more convenient? You have the anthers churning out the pollen, you have the prim pistil taking the center stage and Viola!!! the plant is ready to produce seeds in huge numbers. These flowers, in botanical world, are the monoclinous or perfect flowers and what better to exemplify this class than the rose. Lilies and viburnums are also perfect flowers.

If there are perfect flowers, there have to be imperfect flowers. These are the unisexual flowers that have either the male or female organs. The botanists choose to call these flowers as imperfect or incomplete. Unisexual, imperfect and incomplete-how well this descriptions fits most of us! Many a non-botanists have planted the seeds for papaya and waited endlessly for it to fruit without realizing that the plant is producing only male flower and will never bear fruit. What is more damning for survival as a species than to be rooted to one place and have no female company! But nature is wily and the process of evolution very, very adamant. So there are plants that may bear unisexual flowers......but then they bear both sexes on different branches. Such plants are called monoecious. Better to have some company than none!! Corn, birches, pines are examples of monoecious plants. The pollination amongst these flowers is aided by insects and wind.

One would imagine that the species in which the unisexual flowers occur on different plants altogether would be the most confounded. These plants are called dioecious and include such plants as hollies and papayas. With cultivated/ornamental dioecious plants, one has to make sure that the male and female flower bearing plants are in close vicinity to allow wind/insect pollination in order to set the fruit and seed.

So, there are perfect and imperfect flowers and amongst imperfect there are monoecious and dioecious flowers. It seems that there is a high chance of inbreeding in the perfect flowers , what with the reproductive organs lying in close proximity. Inbreeding, as we all know, is bad news as it limits the variability in the genepool and weakens the chances of survival for a species. Since the time of

The unisexual flowers, of course, allow the mix and match of the pollen and stigmas to enhance the variability in the gene pool. This method poses some constraints like the necessity of closer proximity but is by and large an effective solution. An easier way to ensure cross fertilization is found in plants in which the male and female parts mature at different times. In protandrous flowers, the male organs mature first and shed the pollen before the pistils mature; example Alstroemeria aurea. On the other hand, there are protogynous flowers in which the female organs mature first and they have to be cross fertilized. e. g. Magnolia.

Structural modifications that limit the access of pollens to the stigma of the same flower are also effective in curbing self fertilization. Two lipped tubular flowers from families such as Bignoniaceae and Orchidaceae show bilateral symmetry in which the stigma is positioned right at the entry of the flower causing nectar seeking insects carrying pollen from other flower to affect cross-pollination.

The most sophisticated systems for cross pollination, though, involves a biochemical reaction wherein a chain of reactions ensues after the pollen from the same flower lands on the stigma. The reactions not only recognize that the pollen is from the same flower, but also prevent its further development. Its almost like fingerprinting and arresting the terrorist right at the airport but much more efficient!!

So, the flowers at one level or the other, truly are the charmers that they set out to be. Not all of them are as flamboyant as some of the orchids or as appeasing as the lilies, but they do achieve the end-goal, the purpose for which they are set-forth, i.e. to make more like their own! But all coins have two sides; the beautiful flowers, too, have their counterparts that are neither beautiful nor fragrant. I shall tell their stories next time.